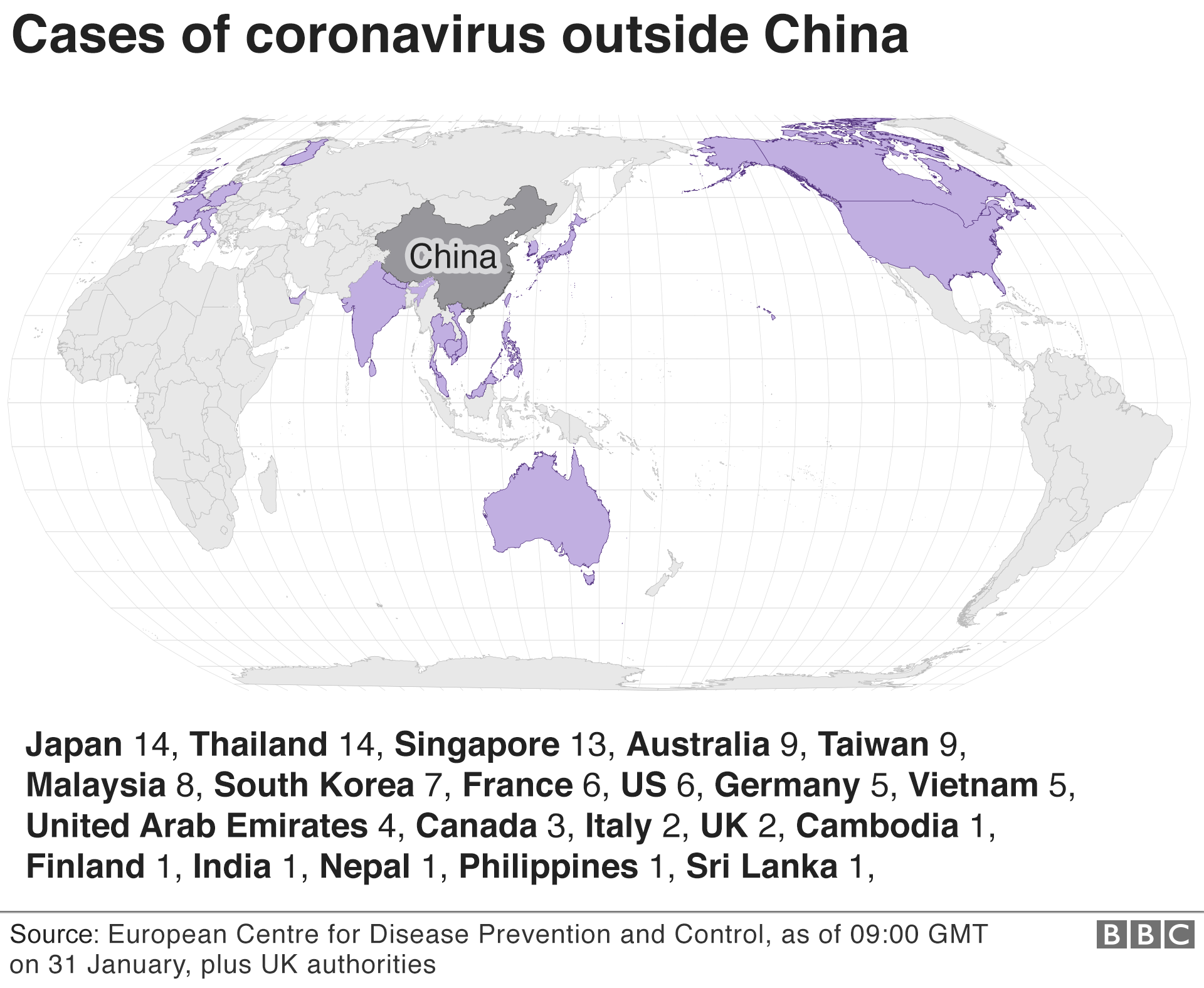

The world is grappling with the new coronavirus, which has spread from China to at least 16 other countries, including the UK.

Outbreaks of new infectious diseases are typically seen as a "one off".

But the new virus - thought to have stemmed from wildlife - highlights our risk from animal-borne disease. This is likely to be more of a problem in future as climate change and globalisation alter the way animals and humans interact.

How can animals make people ill?

In the past 50 years, a host of infectious diseases have spread rapidly after making the evolutionary jump from animals to humans.

The HIV/Aids crisis of the 1980s originated from great apes, the 2004-07 avian flu pandemic came from birds, and pigs gave us the swine flu pandemic in 2009. More recently, it was discovered severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) came from bats, via civets, while bats also gave us Ebola.

Humans have always caught diseases from animals. In fact, most new infectious diseases come from wildlife.

But environmental change is speeding up this process, while increased city living and international travel mean when these diseases emerge, they can spread more quickly.

- Can people recover? And other questions

- Coronavirus: How worried should we be?

- Confirmed coronavirus cases in all China regions

How can diseases jump species?

Most animals carry a range of pathogens - bacteria and viruses that can cause disease.

The pathogen's evolutionary survival depends on infecting new hosts - and jumping to other species is one way to do this.

The new host's immune systems try to kill off pathogens, meaning the two are locked in an eternal evolutionary game of trying to find new ways to vanquish each other.

For example, about 10% of infected people died during the 2003 Sars epidemic, compared with under 0.1% for a "typical" flu epidemic.

GETTY IMAGES

GETTY IMAGES

Environmental and climate change are removing and altering animals' habitat, changing how they live, where they live and who eats whom.

The way humans live has also changed - 55% of the global population now live in cities, up from 35% 50 years ago.

And these bigger cities provide new homes for wildlife - rats, mice, raccoons, squirrels, foxes, birds, jackals, monkeys - which can live in the green spaces such as parks and gardens, off the waste humans leave behind.

Often, wildlife species are more successful in cities than in the wild because of the plentiful food supply, making urban spaces a melting pot for evolving diseases.

Who is most at risk?

New diseases, in a new host, are often more dangerous, which is why any emerging disease is concerning.

Some groups are more vulnerable to catching these diseases than others.

Poorer city-dwellers are more likely to work in cleaning and sanitation, boosting their chances of encountering sources and carriers of disease.

They may also have weaker immune systems because of poor nutrition and exposure to poor air or unsanitary conditions. And if they fall ill, they may not be able to afford medical care.

New infections can also spread rapidly in big cities as people are packed so tightly - breathing the same air and touching the same surfaces.

In some cultures, people also use urban wildlife for food - eating animals caught within the city or bushmeat harvested from the surrounding area.

How do diseases change our behaviour?

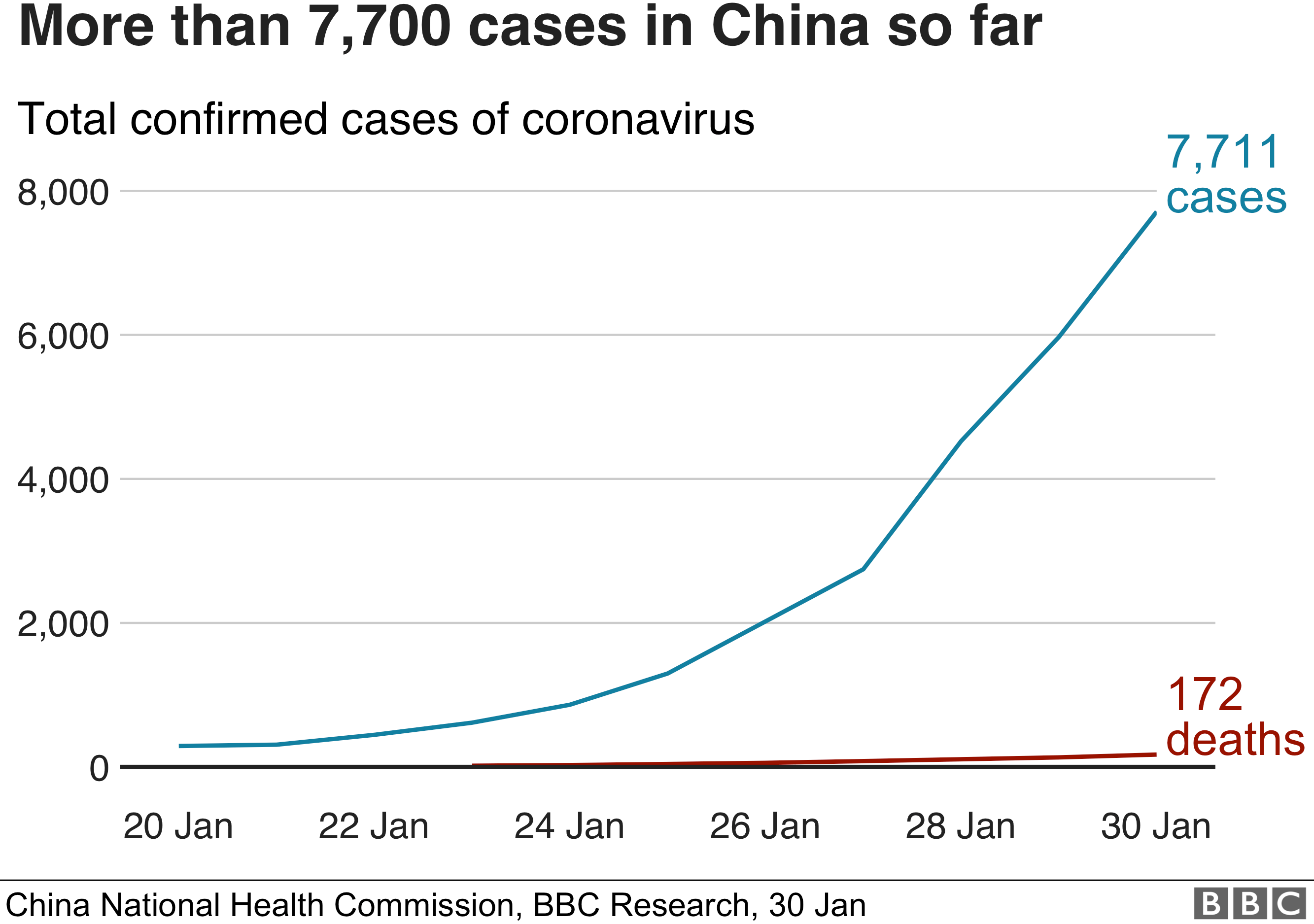

To date, almost 8,000 cases of the new coronavirus have been confirmed, with 170 people thought to have died.

With countries taking steps to stem this outbreak, the potential economic consequences are clear.

Comments

Post a Comment